What is Considered to be Random?

We all have heard of prominent artists such as Jackson Pollock that at first sight on their work did not appreciate the complexity and level of intricacy in their pieces. One, without taste of art (and math!) might foolishly claim that they can reproduce similar patterns since there are actually none! It looks random. but what does “random” actually mean?1 A word that has been thrown around carelessly in daily life which contain variety of meanings. If you think about it really, it’s not so obvious how to actually define “random” rigorously and it’s been a matter of debate for a long time in probability theory.

Autumn Rhythm by J. Pollock

Historically, probability has it’s roots in gambling and safe to say that its classical form was developed by gamblers to enhance their gaming strategies! In addition, probability theory in its early stages was built upon counting and combinatorics. Probability associated to events were simply defined as number of desirable cases over total number of cases which would result in a rational fraction. People would have laughed at you if you’ve said that you have a biased coin with

What Does Probability of an Event Mean in Practice?

A circular approach

What do we mean by having a fair coin? Well, one explanation is that the outcome of the tossed coin is unpredictable to us and we have no preference over each side. This statement, although true, is nevertheless subjective and one might even say they do have the capability to predict the outcome. How can we fact check that? Naturally, one would replicate the experiment multiple times and somehow compare the predicted and real outcomes. This is the point where things get a little circular. In order to give universal meaning to probability you need multiple outcomes of that coin tossing experiment with the same randomness; In other words, generated independently and identically. Randomness is only practically meaningful through replication and that was the main motivation to define it theoretically in such a way to conform to this idea.3

This sort of argument is analogous to say 1 object is only meaningful if there exists 2 of them besides together, moreover 1+1=2. Thus, 1 is tied to the whole integer system and they are not meaningful individually.

A Rigorous Attempt to Define Randomness

Suppose

Definition. A binary sequence

- (Frequency Stability) let

- Suppose

As discussed previously, the first property is known as the Law of Large Numbers. The second property, although looks mysterious, simply states that valid subsequences should also satisfy frequency stability since after all they are a sub-collection of i.i.d. random variables. It also has an interpretation in gambling called Laws of Excluded Gambling Strategy Strategy. Indeed, every subsequence won’t work; For instance, if you look at the subsequence that they are all 0s or all 1s then stability will not hold. In the rest of this article we will adopt this notion of randomness as our definition.

Perception of Randomness

In this section we are mainly interested in understanding how human intuition perceives randomness. What type of features in a sequence would trigger human’s intuition as chaotic? Suppose I give you a binary sequence and ask you to judge about whether this sequence was generated uniformly random or not. Can you find meaningful patterns in it? Which one of the following sequences appears to be random in your perspective?

Streaks of What Length Should we Expect In a Random Sequence of Length n?

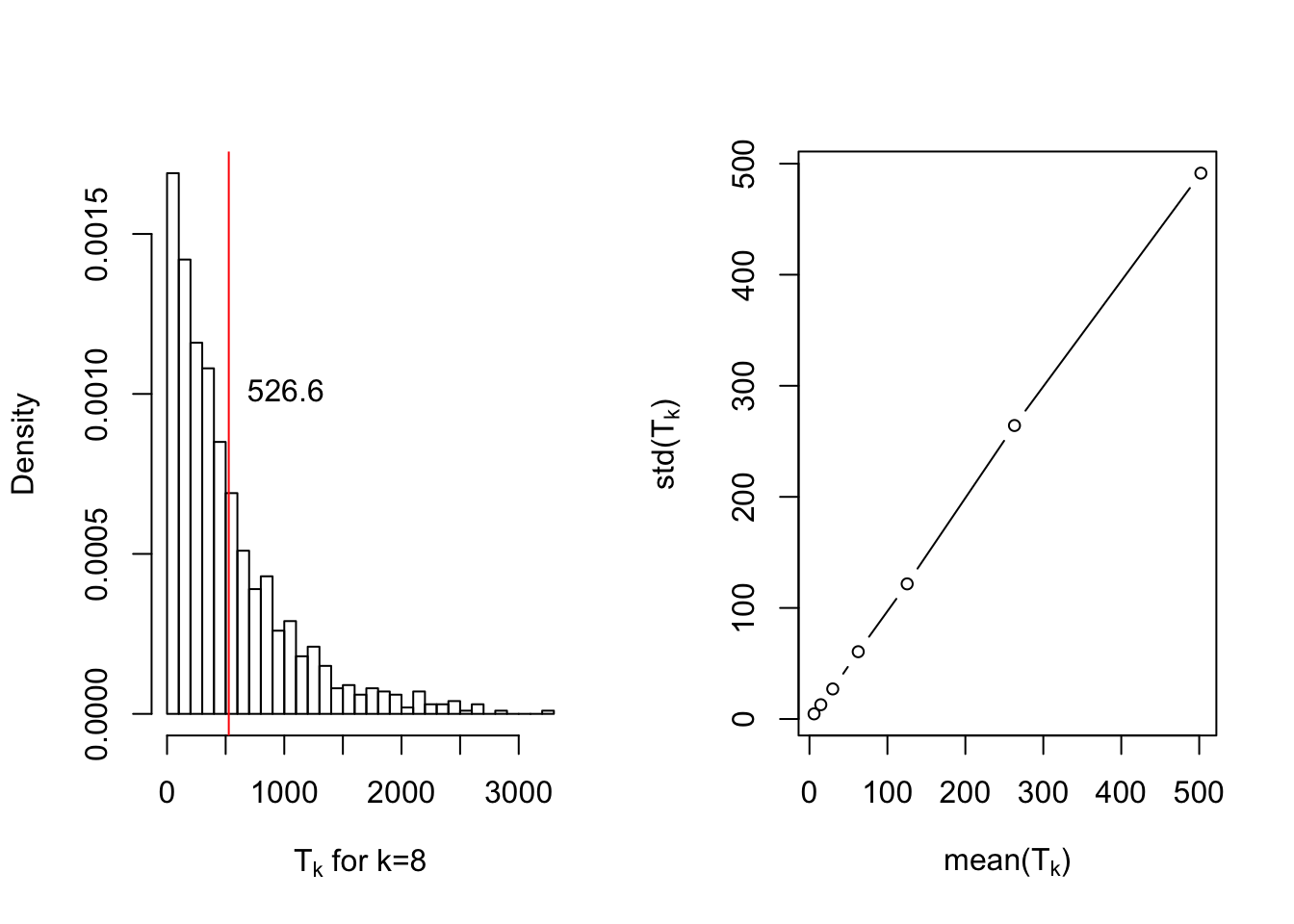

Let us define stopping time

At this point, an interesting question would be whether this random variable is concentrated around it’s mean or not? if so, how well? Apparently this does not seem to be true and

In conclusion, one should expect a streak of length

Wald and Wolfowitz Test

Myriad number of tests were developed to quantify randomness in a sequence. After all, this is an important problem since fields such as cryptography relies heavily on the randomness assumption which guarantees existence of codes that are intractable to break. Some tests are based on the longest run in the sequence, while others as in Wald and Wolfowitz test are based on the number of runs.

Instead of binary, let us assume

| First.Sequnce | Second.Sequnce | |

|---|---|---|

| P Value | 0.0412268 | 0.6830914 |

This does not necessarily mean, our test was wrong or we got bad luck, but could simply mean that our intuition is not fully aligned with the intended notion of randomness. As much as human perception of randomness could be biased, generating something that looks random is difficult. It is also worth mentioning that this entire discussion was 1-dimensional and mainly focused on 1-dimensional local features such as streaks. However, one should expect novel and astonishing phenomena to occur even in 2-dimensions since human intuition is now equipped with 2-dimensional local neighborhood.

Phenomena such as percolation which states that there is a path from center to the border of a random 2-dimensional matrix with black and white pixels is of particular interest to me and I’ll write about them in the near future.

Phenomena such as percolation which states that there is a path from center to the border of a random 2-dimensional matrix with black and white pixels is of particular interest to me and I’ll write about them in the near future.

Some Laws and Problems of Classical Probability and How Cardano Anticipated Them↩

It is fair to say independence itself is not well defined in practice. Do we mean to conduct our experiment with exact same conditions? Shouldn’t that make the outcome identical to the previous experiment? This is indeed a matter of debate in philosophy of probability, and frankly, don’t know the answer to it.↩

A pedantic reader might also be skeptical about this statement since it’s not trivial to define independence over an infinite collection of random variables and it’s true. It requires further knowledge in measure theory but for now consider it means every finite sub-collection should be independent↩

This reset argument is rather technical and it’s due to the Strong Markov Property of discrete Markov Chains which states that